“I’m the baby. I’m number 13,” says Sandra McDonald Jewel.

“I’m the baby. I’m number 13,” says Sandra McDonald Jewel.

“And I’m the … ” Shirley McDonald Douglas begins. She turns toward her sister Sandra.

“Don’t look at me,” Sandra says laughing.

Shirley turns back confidently. “I’m number 10,” Shirley says.

They both look to the next in line. Sitting beside Shirley is Curley. He sits in a plain T-shirt and weathered blue jeans with a crease down the front from an iron. He breaks the conversation with occasional funny comments that will get a laugh from all of his other siblings. They all refer to him as the comic. His deep Southern drawl adds to each punchline without so much as a change in his facial expression.

“I think I’m number nine,” Curley says. He stops and pulls a toothpick from his mouth. “Wait a second, I can’t be number nine.”

Everyone in the room busts out laughing.

Sitting arm to arm are seven of the McDonald siblings. There were 13 originally, and most of the siblings keep the order by knowing which of the other siblings they fall between.

“You are number eight, Curley,” Shirley says laughing.

As they count down the line, the debate about numbering continues — six, seven, five, no, maybe it’s eight. Each time one announces their number in line, another corrects with the order of the siblings’ names.

“You in-between June. You are number six,” one counters back to Margaret. And they all laugh.

Curley makes a joke about them trying to figure out the pecking order and being elderly. Then they’ll all stop for a second and start counting siblings out loud between the laughing.

“I need more fingers,” says Margaret McDonald Micheaux. “It’s enough to confuse you.”

The McDonald family members span the ages from 70 to 85. They have seen the tides of change throughout the decades in North Carolina having lived here from 1930s-1940s on and off. Growing up just a stone’s throw from Fayetteville, these kids, now mostly grandparents themselves, belonged to a family of sharecroppers in Eastover. Currently, all the siblings still living — nine in total — live in Eastover except Shirley who resides at a senior center in Fayetteville.

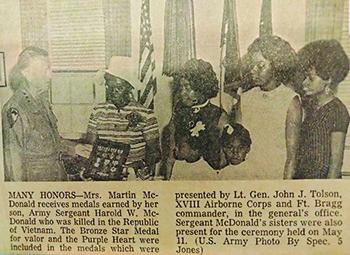

The group tries to get together once a month for birthdays or celebrations, admittedly happening less frequently since “the virus,” as they term it. Among these celebrations is always an event for Veterans Day. The siblings go to breakfast and then to the Airborne Museum to place flags in honor of Oliver and Martin Jr., who both were drafted during the Vietnam War, and Harold, who died in Vietnam saving another soldier’s life.

In Curley’s hand is a picture of a young man with a thin mustache in Army fatigues; composed next to the picture is an onslaught of awards. With just a question about Harold, the laughing suddenly stops. A stillness grows in the room, a stillness defined by heartbreak.

“Everybody loved him,” Joyce says. “When we lived in Brooklyn, the kids on the block on Saturday mornings would throw pebbles at his window so he could come down. He would spend the days out there playing with them. Old people loved him and young people loved him.”

The rest of the siblings nod their heads in slow agreement. The room is silent for the first time since they arrived.

“He was just awesome,” Shirley says. “He was cool. He was debonaire. He could dress like nobody else. He could sing.”

Shirley sits forward and places a hand on her knee. She retells the story of how he died in the war, pulling someone else off what she called a “booby trap.”

“I wanted to go back but I knew I couldn’t do nothing about it,” Martin Jr. says recalling Harold’s death. “I thought about it a lot.”

The sadness in his voice as he speaks is palpable. The death of their beloved brother has defined the McDonald family in many ways. It also brings them together every year to celebrate the life of Harold and tell the stories of how much life he lived in those 21 years. When they speak about him, a smile naturally draws across their faces.

In the 1960s, Curley and others left for New York City. Many of the McDonald siblings traveled to parts of New York or New Jersey. Tired of the sharecropping life, they looked north to find “good jobs.” Joyce, Harold, Curley, Shirley and a few others went north for some years to find different lives than they had in North Carolina.

“They didn’t have any rich black farmers,” Joyce says.

“You get 20 dollars a week. That’s all you made,” Curley joins in.

“You know, we didn’t know we were poor,” Shirley says.

Their parents, Martin Sr. and Pearl McDonald, came from big families, too. Martin Sr. did sharecropping while Pearl cooked, worked in the school system and occasionally watched other children. Martin Sr. was fun, loved to dance but had no arm for discipline.

“Mother did,” Joyce says. “She was loving but she was stern.”

“Yeah, to the others that needed it,” another sibling chimes in. They all chuckle again.

“All except me,” Margaret says, laughing. Curley rolls an eye and gives a soft laugh. Margaret ignores him.

“I try not to talk to him,” Margaret jokes about Curley.

“I don’t care,” he says under his breath.

“I know you don’t,” she laughs.

“That way I don’t have to answer questions,” Curley said.

The siblings all grew up working out on the farm except for Sandra who recalled coming along anyway because she couldn’t be left home alone. Margaret stops the chatter for a moment to debate on whether she worked on the farm and Martin Jr. chimes in that if she had done it, “you’d have known it.” The group laughs for a moment.

When speaking, each sibling goes back and forth between calling their siblings by their real names and nicknames. They begin to talk about the nicknames they were all given.

Martin Jr. became just June for Junior. Curley is the comic. Oliver is the quiet one or Marshal Dillon due to his non-rushing nature. Shirely became Gal. Curley jokes that anything that happened to pop out of their mouths was what they would be called. The nicknames ran fast and loose in the family.

“I got one word that would go with two,” Margaret says.

“Scaredy cat,” Martin says back, laughing.

“She sees a snake on TV and she starts running,” Curley says. The rest of the group starts laughing now. “Ah, come on now. What is that?”

“I got another name, meanie.” Martin Jr. points to Margaret.

“I guess I just got that voice sometimes,” Margaret answers.

“What voice?” Martin says.

“I dunno. That voice.” Margaret replies.

The conversation naturally comes back to Harold and the group silences for a second, then calmly a few of them say the word that they think embodied him — “cool.” Many of the siblings say it at the same time as if the feeling about their brother is completely unspoken but mutual among them.

“He would probably have ended up as a Motown singer if he had come back,” Joyce says. “He used to be out on a Saturday. You could hear him a block and a half away singing. You could hear windows going up and people telling him to be quiet.”

Right before going to Vietnam, Harold wrote a letter to Motown and was accepted to come audition, Joyce recalls. Curley joins in and talks about Harold singing at the Apollo on Wednesday nights.

Harold is buried out in Rockfish Cemetery on 301 near his mother and father. Martin Sr. died in 1994 and Pearl in 2001.

“I was out there today,” Martin Jr. says.

“All the time,” says Curley.

This year they plan to host the same tradition of breakfast and then flag placement in downtown Fayetteville. They will laugh. They will share stories. They will ping off each other’s jokes as quickly as any siblings. And they will remember Harold.

“It makes you stay appreciative,” Sandra says. They all smile and look around the room. They are as close as any siblings could be.

Oliver, who is true to his quiet moniker, hasn’t spoken much during the talks. He then says quietly after looking around, “We all love each other.”