- Details

-

Tuesday, 06 January 2026

-

Written by Jimmy Jones

A Storyteller, a Community, and 30 Years of Gratitude

Jimmy Jones' connection to Up & Coming Weekly began in 2007 when he attended a writing class at FTCC. His instructor, the late and great Melissa Clements, encouraged him to share his stories and suggested he reach out to us. He did—and soon became a fixture here, chronicling life on the road and the stories that shape and inspire our community.

Jimmy has a storyteller’s eye and a gift for uncovering meaning in the ordinary. One unforgettable series followed his motorcycle ride to the Arctic Circle, where he carried a copy of Up & Coming Weekly and a plush toy of the Kidsville News! mascot, Truman the Dragon, sending photos back to our readers along the way.

He also partnered with us on many company events like the annual Hogs & Rags Charity Motorcycle Ride, helping raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for local charities and the Kidsville News! literacy programs.

Jimmy’s writing is authentic. His signature style blends humor, honesty, and what he calls “the question behind the question”—a thoughtful approach that invites readers to look a little deeper while enjoying the ride. We are proud to continue sharing his insights and storytelling with our readers throughout the Fayetteville and Cumberland County community.

As you enjoy Jimmy Jones’ 2025 Year in Review, we invite you to look ahead with us to a wonderful and exciting 2026 as our nation celebrates America’s 250th Anniversary. This milestone year also marks Up & Coming Weekly’s 30th Anniversary as your trusted local community newspaper.

Thank you for reading, supporting, and believing in Up & Coming Weekly. We couldn’t have done it without you.

—Bill Bowman, Publisher

Some years whisper. Some years tiptoe. 2025 kicked the door in and asked for coffee. It was not subtle. It was not quiet. And depending on where you stood politically, it was either the dawn of American greatness or the end of Western civilization. There was no middle ground.

Some years whisper. Some years tiptoe. 2025 kicked the door in and asked for coffee. It was not subtle. It was not quiet. And depending on where you stood politically, it was either the dawn of American greatness or the end of Western civilization. There was no middle ground.

Donald J. Trump was sworn in again, this time as the 47th President, and instantly the country split into its two favorite camps. There were those ready to crown him a savior and those ready to blame him for global warming, rising sea levels, and the McFlurry machine being down. The new business model for the media was simple: praise him like you are auditioning for state television or hate him so loudly that dogs three counties over can hear it. Clickbait became the national sport. Headlines were not written, they were weaponized.

But for all the noise, real things happened. Big things, messy things, and a few that even counted as good news.

Western North Carolina spent 2025 clawing its way out from under the destruction of Hurricane Helene. The storm hit hard, but the political aftermath hit harder. Regulators slowed recovery by blocking people from working on their own damaged property at the exact moment families needed speed, not signatures. But citizens refused to quit.

Neighbors helped neighbors. Volunteers from across America rolled in with tools and grit, pushing forward despite the delays. The new Trump administration released billions for Helene recovery, sped highway and housing money into Western North Carolina, and cut enough federal red tape around debris and permits that work finally began to match the promises.

There is still much work to be done, but for many people, the response restored something deeper. It reminded them of the determination of ordinary Americans and the old spirit of goodwill that still shows up when things are at their worst.

Early in the year, Trump bombed Iran’s nuclear program in a strike few saw coming. He negotiated the release of every American held by Hamas and brokered a fragile peace treaty for Gaza. Back home, he pardoned more than 1,600 Americans in a single year, which either restored justice or set it on fire.

Congress also managed something. It created the longest federal shutdown in American history. Democrats dug in so hard that Trump found it easier to negotiate with terrorists than with Congress. When a government stays closed longer than seasonal beach rentals, it is no longer a shutdown. It is a lifestyle choice.

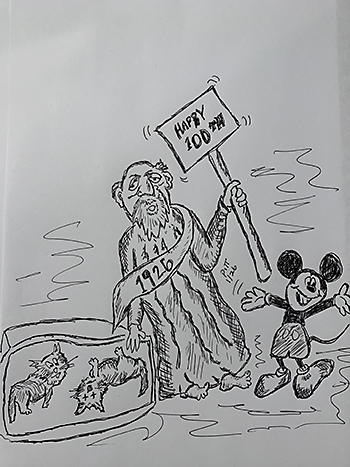

This was the year the penny died. After decades of being ignored on sidewalks and rejected by vending machines, the last penny rolled off the mint. Even the currency was tired of inflation.

The economy did what the economy does. It looked great on paper while insulting everyone at the grocery store. Jobs climbed, markets hit new highs, and inflation cooled, but try telling that to someone staring at the price of a carton of eggs. It was the best economy ever, except in the places where you spend money.

Tariffs became Trump’s foreign policy yo-yo, swinging in every direction as he used them to drag world leaders back to negotiation tables, which they thought they had left behind. Economists cursed, diplomats blinked, and somehow it kept working.

Trump insisted prices were down, but most Americans did not feel it. Inflation may have cooled, but everyday costs still stung. Part of the problem is our slide into a digital-first economy. Tap-to-pay, online checkout, and QR menus all come with invisible fees, and retailers quietly tack on an extra few percent. It is not on the tag, but it is there. The math says we should be winning. The checkout screen says otherwise.

2025 was a big year for “science,” or at least the kind billionaires call science. Jeff Bezos sent five women on a Blue Origin flight and proudly labeled them astronauts, even though NASA uses a much stricter definition. Many praised the crew’s “scientific contributions.”

Engineers nodded in respect while Americans wondered how the capsule’s hatch survived space after Bezos botched a photo op that showed the door swinging open more easily than a cheap shower curtain.

While the rockets flew, artificial intelligence crept into every corner of daily life and became the new electricity. We used it for simple questions, medical advice, legal explanations, and turning everyone into an expert on trivia night. Businesses baked new AI into every piece of software. The government was still trying to remember how to spell AI when Trump and a guy named Elon dropped bombs on the federal workforce with “Fork in the Road,” “Five Bullets,” and a wave of reductions that made clear nobody in government was untouchable. Bureaucracy suddenly found itself replaced by a single brutal metric: return on investment.

Americans also found time for protest, and the most successful one of the year was the No Kings movement. It worked beautifully, since as of this writing, America still does not have a king. Speaking of kings, Jesus made quite a comeback in 2025. Churches across the country reported a quiet revival, especially among Gen Z. Some say the rise started after the assassination of Charlie Kirk. Others credit the success of The Chosen television series. Jesus said it was the work of the Holy Spirit. However it happened, faith found its way back into the headlines.

In foreign affairs, Trump renamed the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America. He then amassed the largest military buildup off the coast of Venezuela since anyone can remember, making geography teachers relevant again. He also brokered a peace agreement between Israel and Hamas. Whether it lasts remains to be seen, but for a brief moment, the Middle East took a breath instead of throwing something.

The Epstein Files came to a head. The story began quietly under the Bush Justice Department. It exploded under Trump’s in 2019, when the Southern District of New York brought charges and Epstein went to jail. It spiraled into the most controversial in-custody death of the century. When the files finally dropped in 2025, no one got the closure they wanted. The case was such a mess that anyone even remotely connected to it walked away looking contaminated.

America also spent the year arguing with itself at a level that would impress a dysfunctional family reunion. Public trust in the federal government sank so low that even after Trump promised transparency, half the country still waited for the fine print. Conspiracy theories filled the gap. It reached the point that if the media made up a story that Lee Harvey Oswald had shot Charlie Kirk from beyond the grave, half of America would fight the other half. That was the national mood. Suspicious. Exhausted. Constantly bracing for the next twist.

Charlotte spent 2025 painting a black eye on North Carolina. A young girl was stabbed on the light-rail train by a repeat offender, landing like proof that their courts were turning dangerous criminals loose. Raleigh passed new laws forcing local jurisdictions to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement, and Charlotte pushed back. The atmosphere got so tense that the running joke was that 7-Eleven took down their ICEE machines to avoid bad optics.

Back home in Fayetteville, history went out like a boomerang, swung wide, and found its way right back where it started, bruising some egos in flight.

The post, formerly known as Fort Bragg and then Fort Liberty, reverted to Fort Bragg.

Mayor Mitch Colvin secured his fifth term, proving that Fayetteville loves consistency or simply does not have the stamina for another campaign season.

The biggest local mess of the year was the Crown Event Center, a roughly 145 million dollar downtown performing arts project once billed as the county’s next crown jewel. Instead, it burned through about $36 million in planning and site work before the newly elected Cumberland County Board of Commissioners weighed in with justified suspicions.

After prudent vetting, vision, and common sense, the board voted in June to shut the project down and invest instead in rehabilitating and refurbishing the existing Memorial Auditorium, hoping it will become the spark that ignites commercial development and eliminates one of the ugliest and most blighted areas of Fayetteville.

No event center will be built on that vacated lot, leaving behind frustration and the lingering question: “What will go there?” It stands as a costly lesson in what happens when oversight, transparency, and alignment are overtaken by unchecked ambition.

Many Americans have become increasingly concerned about crime, jobs, AI, and housing shortages. Millions of unauthorized immigrants arrived in recent years, while tens of millions more entered legally on visas or as new citizens. Assimilation has given way to a patchwork of tribes, languages, religions, cultures, and geographic enclaves that no longer pull toward a single American identity. In the name of freedom and equity, the unifying force that once shaped newcomers into Americans is quickly fading. It leaves many wondering whether we are slowly destroying the American way from within. History will be the judge.

We made it through a loud, wild, unforgettable year. The Declaration of Independence reminds us that we are endowed with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As we head into 2026, America will celebrate its 250th birthday, the Semiquincentennial, a reminder that we are the beneficiaries of 250 years of sacrifice, perseverance, and faith, and stewards of what must endure for the next 250. For 2026, we hope you find a way to pursue your happiness to the fullest.

May God bless you and your family. Happy New Year.

- Details

-

Tuesday, 06 January 2026

-

Written by John Hood

While our state continues to best most others in economic performance, not all our households and communities are sharing in North Carolina’s prosperity. Some are struggling to replace lost jobs with new ones. Other folks are gainfully employed but see their real incomes being eroded by the rising costs of housing, health care, transportation, and other necessities.

While our state continues to best most others in economic performance, not all our households and communities are sharing in North Carolina’s prosperity. Some are struggling to replace lost jobs with new ones. Other folks are gainfully employed but see their real incomes being eroded by the rising costs of housing, health care, transportation, and other necessities.

Washington certainly needs to get its act together. State and local policymakers can also do more to provide the high-quality education and infrastructure needed to compete for tomorrow’s industries. But the primary drivers of a healthy economy are private, not public. And right now, too many of them are constrained, diverted, or blocked by unwise regulation.

These economic frictions — let’s call them choke points — keep existing businesses from growing and hiring, keep new businesses from starting, and keep producers and consumers from realizing the full benefits of competitive markets.

Rigid zoning and permitting delays, for example, continue to deter homebuilders from supplying enough housing stock to meet demand. Occupational licensing makes it unnecessarily expensive and time-consuming for North Carolinians to change careers or launch new enterprises. And outdated state laws limit competition among hospitals and health providers. As a result, North Carolina’s health care costs exceed those of many of our peers.

A recent report by The Charlotte Ledger spotlighted another painful choke point: car and truck prices. For decades, North Carolina law forbade automobile manufacturers from selling their products directly to their customers. Dealers insisted the result wasn’t a system rigged in their favor, since they compete intensely among themselves to sell vehicles and services to consumers.

If this were true, however, there’d be no need for such a law! If independent retailers deliver real value to motorists — a proposition that doesn’t strike me as implausible, actually — they can surely prove their worth in a fully competitive market in which consumers can choose how and from whom to purchase vehicles and services.

In 2019, the General Assembly loosened the automobile choke point, however slightly, by allowing Tesla to open five dealerships in North Carolina. Now that other new companies are entering the hybrid and electric vehicle space, however, the Tesla exception no longer makes sense (and is vulnerable to legal challenge). Many states — including the likes of Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida — already allow all EV comers to sell directly.

North Carolina ought to join them. Indeed, I’d like to see our state eliminate the choke point entirely by repealing our dealer franchising laws and allowing manufacturers of all vehicle classes to strike whatever distribution deals they wish. A radical suggestion? Not really. A 2022 poll found that 83% of North Carolinians favored “allowing North Carolina drivers to purchase a vehicle straight from the manufacturer, and to receive routine service and repairs on a vehicle from the manufacturer, without having to go through a dealership.”

A 2024 report for the U.S. Department of Justice projected that eliminating artificial restrictions on car sales wouldn’t just put downward pressure on prices. “Perhaps the most obvious benefit,” wrote Gerald Bodisch, an economist in DOJ’s Antitrust Division, “would be greater customer satisfaction, as auto producers better match production with consumer preferences ranging from basic attributes on standard models to meeting individual specifications for customized cars.”

As for dealer concerns about potential mistreatment, Bodisch concluded that “competition among auto manufacturers gives each manufacturer the incentive to refrain from opportunistic behavior and to work with its dealers to resolve any free-rider problems.”

“Consumers are used to the idea that they get to decide,” argued University of Michigan law professor Dan Crane. “That they get to figure out, ‘Do I prefer to bargain with a dealer on a lot or do I get to buy it directly from the manufacturer?’”

Whether in real estate, labor markets, health care, or consumer products, regulatory power ought to be used to promote transparency, combat fraud, and protect public health and safety. To go beyond these legitimate ends is to regulate too tightly. Time to loosen.

Editor’s note: John Hood is a John Locke Foundation board member. His books Mountain Folk, Forest Folk, and Water Folk combine epic fantasy with American history (FolkloreCycle.com).

It was 250 years ago last week that a displaced governor issued a proclamation intended to restore him to power in North Carolina. Instead, it led to the first major engagement of the Revolutionary War in the Southern colonies — and a decisive defeat for his cause.

It was 250 years ago last week that a displaced governor issued a proclamation intended to restore him to power in North Carolina. Instead, it led to the first major engagement of the Revolutionary War in the Southern colonies — and a decisive defeat for his cause.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?