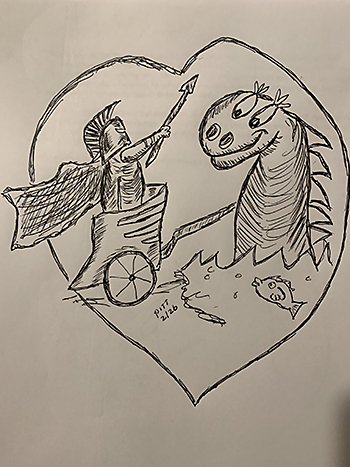

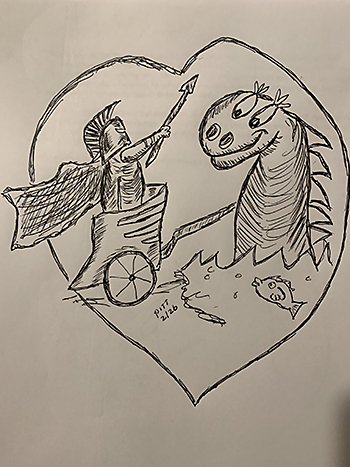

Greek mythology: What’s love got to do with it?

- Details

- Tuesday, 17 February 2026

- Written by Pitt Dickey

Last week was the most fraught time of gift-giving of the year. Did you and your significant other survive Valentine’s Day with your relationship intact? Did you provide a gift that proved you were worthy of sleeping indoors? Gifting at Valentine’s Day is exponentially more difficult than Christmas or even birthdays.

Last week was the most fraught time of gift-giving of the year. Did you and your significant other survive Valentine’s Day with your relationship intact? Did you provide a gift that proved you were worthy of sleeping indoors? Gifting at Valentine’s Day is exponentially more difficult than Christmas or even birthdays.

One false step and you could be in the back yard sleeping with the Racoons. For the sake of making you feel better about your romantic shortcomings, today we shall consider the tragic love story of Phaedra and her stepson Hippolytus.

However your Valentine’s Day turmoil turned out, it had to be better than Phaedra (who we will call Fay and Hippolytus who we will call Hippo). Greek mythology is full of wild and crazy family antics. Like marriages of folks in West Virginia and Kentucky, love affairs in Greek Mythology require elaborate diagrams of family trees to sort them out.

Here is the background. Try to follow along. King Theseus kidnapped Hippolyta, the Queen of the Amazons. Whoopee was made with her, resulting in Theseus’ son Hippo.

Theseus was a major dude, helping Hercules steal the Queen of the Amazons' utility belt and killing the Minotaur. Theseus subsequently fell for Fay and married her. Hippolyta was not amused at being dumped. She led a group of Amazons to attack Theseus’ wedding reception. In the melee of this original Red Wedding, Theseus killed Hippolyta.

Unfortunately, Fay fell in love with her stepson, Hippo. This scenario has led to numerous versions of stepmom/stepson interactions on certain adult websites. (A guy told me about this.) Fay tried to seduce Hippo to no avail. Hippo had sworn to preserve his virginity forever in honor of Artemis, the Goddess of chastity and childbirth, among other areas. When Hippo turned Fay down, she was sorely vexed.

Remember the old saying about Heck hath no fury like a woman scorned? That wasn’t the half of how Fay felt after Hippo’s rejection. She was substantially unhappy.

There are two versions of what happened next.

Version one: Fay knew if Hippo told his daddy, Theseus, about Fay hitting on him, there would be big trouble. Knowing the best defense is a good offense, Fay lied to her hubby, telling him that Hippo had tried to rape her. Theseus believed her accusation.

He had been previously given three wishes by Poseidon, the Sea God. He used one of his wishes to curse Hippo to death. One day, Hippo was minding his own business while racing his chariot along the shore like folks used to do at Daytona Beach. It was a lovely day. Nothing could spoil it. Uh Oh! Poseidon sent a Sea Monster out of the ocean up onto the beach. This was no friendly sea monster like Cecil the Seasick Sea Serpent.

No siree, Bob. This was a high-efficiency, full-throttle, torque-heavy, supercharged, mean, ugly, and nasty Sea Monster.

The Sea Monster freaked Hippo’s horses. They stampeded, breaking the chariot into pieces. Hippo got tangled up in the reins and was dragged to a gooey death. Like all bad things done in the dark, Fay’s lies eventually come out in the light. She couldn’t stand the heat and hung herself.

Version Two: Hippo is still a follower of Artemis, the Virgin Goddess. He swears he will never love or marry to honor Artemis. He also refuses to worship Aphrodite, the Goddess of Love. Aphrodite gets wind of this apostasy and decides to punish Hippo. She puts a curse on Fay to make her fall in love with Hippo. Fay knows hers is a love that dares not speak its name. She falls into a deep depression, refusing to leave her bed or eat. Fay eventually confides in her nurse about being sweet on Hippo.

The nurse tells Hippo, attempting to save Fay’s life. Hippo again rejects Fay.

Fay knows she will face consequences now that the story is out. She plans to commit suicide and writes a letter to Theseus falsely accusing Hippo of seducing her. She hangs herself, holding the poison pen letter in her cold, dead hand. After Theseus reads the letter, he calls in his wish from Poseidon, resulting in the Sea Monster scaring Hippo’s horses, causing Hippo’s death on the beach.

Gentle Reader, don’t you feel better now about your own Valentine’s miscues? Your mistakes pale in comparison to Greek Mythology.

You did not create a ravenous Sea Monster at Myrtle Beach. The Schadenfreude produced by this column will cure your depression resulting from Valentine’s Day errors. It’s cheaper than Rexulti and has no scary side effects.

You’re welcome.

(Illustration by Pitt Dicky)

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?